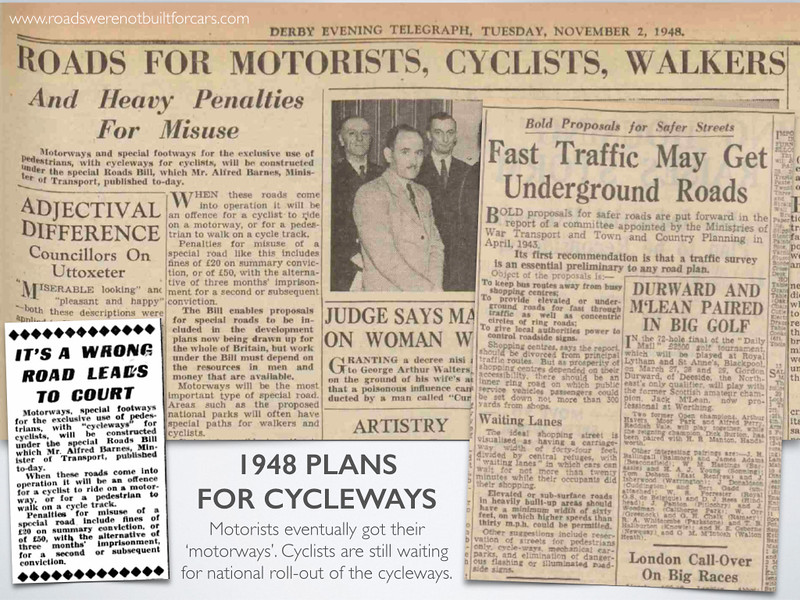

In 1948, Britain’s Minister for Transport Alfred Barnes introduced the Special Roads Bill. This would – eventually – lead to the creation of Britain’s motorway network. But where are the cycleways promised in the 1948 plans? Apart from the New Towns – including Stevenage, with its extensive and dense network of cycleways – these ‘special roads for cyclists’ were never built. Why? The Minister for Transport said provision for cyclists was a local matter. This is exactly the same reason wheeled out today. Infrastructure for cars is “national”; infrastructure for bicycles is “local.”

The Special Roads Bill came before Parliament on 30th September 1948. Its purpose was “to provide for the construction of roads reserved for special classes of traffic; to amend the law relating to trunk roads; and for purposes connected with the matters aforesaid.” The Special Roads Bill became the Special Roads Act in 1949. Special roads for cars could now be constructed. The first wasn’t started until 1958 but they came thick and fast in the 1960s. It was a mature network by the end of the 1970s.

Back in 1948 the newspapers reported that the Special Roads Bill would see the building of cycleways, too. And just as cyclists would be fined for riding on motorways, pedestrians would be fined for straying on cycleways.

Introducing his Bill, Alfred Barnes said:

It will be a mistake for anyone to assume that the Bill is promoted to satisfy the selfish interests of the private motorist. It is nothing of the kind. It is often overlooked that nowadays we are all motorists, whether or not we drive a private car. Everybody travels on buses or coaches and the greater proportion of our domestic and personal needs are delivered by motor van.

But, and here’s the kicker, he believed national highway authorities should be in charge of major motoring roads, but “special roads for pedestrians and cyclists” should be provided by local highway authorities. And such “special roads” for users other than motorists were clearly deemed to be recreational, rather than everyday practical:

I should emphasise … under the powers given to them to construct a special road, highway authorities could determine that the only classes of traffic using that road should be motor vehicles. These same powers can —and, I sincerely hope, will — be used by county highway authorities for the construction of special roads for pedestrians and for cyclists — across for instance, a national park, along a river bank, across mountain, moor, or the coast line. [This] responsibility will rest upon local highway authorities, who ought to meet the cost of special roads of this type. The cost of constructing and maintaining the special types of roads for hikers or cycle paths for cyclists will not represent any very considerable capital outlay or annual cost for maintenance. At a time when the State, by this Measure, visualises the construction of these motorways at the capital cost I have mentioned, for the purpose of relieving the local authority of a good deal of the cost of other highways, it is not unreasonable to suggest that highway authorities should use these powers for the purpose I have indicated, especially as the advantages to be derived will be enjoyed largely by the residents in their own localities.

Mr. Walkden, the MP for Doncaster, stressed that if cyclists did get cycleways, they ought to be fined if they choose not to use them, despite the fact the pre-war Alness parliamentary report had found that the cycle paths constructed in the 1930s were universally poor:

I hope the Parliamentary Secretary will explain later on whether, in passing this Measure, we are giving assent to the principle that if a cyclist fails to use a roadway provided by the nation, or by a local authority with the blessing of the nation, we shall impose a punishment of up to £20….At least in one country I have visited, which has a considerable mileage of cycle tracks, it is a punishable offence for cyclists to fail to use these particular cycle tracks. Cyclists there can be dealt with severely…It is laid down specifically that we are to provide cycle tracks, but I find that in the case of a road along which I pass almost every day — the Sutton by-pass — the cyclists disregard the cycle tracks provided on either side, with the result that the ‘bus drivers use the sort of language only London ‘bus drivers can use…If we are to lay down these roads for a particular class of user, then everyone concerned should understand the law.

The Alness report had recommended Britain should build a network of cycleways but post-war austerity killed off these plans. But while there would be no building of bike paths, post-war politicians were still urged to get cyclists off the roads “for their own safety”, even though cyclists were still by far the most numerous actors on the roads, probably because cyclists were the most numerous actors on the roads. Faced with calls to take action, politicians did what they often do best: they did nothing. Cyclists, en masse, were still a force to be reckoned with. It was easy for politicians to pick a fight with the CTC or National Cyclists’ Union, these organisations were tiny compared to the rich motoring organisations, but to impose restrictions on all of the country’s 12 million cyclists would have been folly. (One of the witnesses to the Alness committee said as much: “[Cyclists] ought to be forced to use [tracks]. The only reason they escape is because there are so many of them. There is a vague idea on the part of Governments that they would lose the cyclists’ vote,” claimed Lord Newton who repeated the claim when the report was published: “[cyclists] form a very formidable body, of which all Party politicians are very much afraid. That is the sole reason why they have not been regulated up to now, and I hope sincerely that that state of things will come to an end.”)

By not banning cyclists from the road, as so many organisations demanded, politicians avoided antagonising cyclists. By building faster roads with no cycle facilities on them it was motors which did the antagonising, not politicians. 1949 was to be the peak year for cycling in Britain. In the 1950s the increasing numbers of motor cars slowly forced cyclists off many roads, and not just the arterial ones.

Motorways – roads long championed by the CTC as a means of removing fast-moving traffic from the ordinary roads of Britain – started to be built at the end of the 1950s but it was well into the 1960s before motorway-mania took hold, with many trunk roads also being built or old roads widened, straightened and made less friendly for cyclists. None of the new arterial roads had cycle paths built beside them.

While cyclists were largely forgotten by town planners in the 1950s there were exceptions: new towns Stevenage, Harlow and Milton Keynes were veined with bike paths. (Stony Stratford, just north of what would become the new town of Milton Keynes, was one of the other locations where bike paths were first trialled. A one mile cycle track had been laid on the Stony Stratford to Wolverton Road in 1934-5, it’s now a footpath.) Workers who lived in Jarrow and Wallsend were provided with the Tyne Pedestrian and Cyclist Tunnels, a wonderful piece of capital-intensive, protected infrastructure, still in use today. The tunnel was opened in 1951, sixteen years before the motor vehicle tunnel. At its peak, 20,000 cyclists and pedestrians used the tunnel each day.

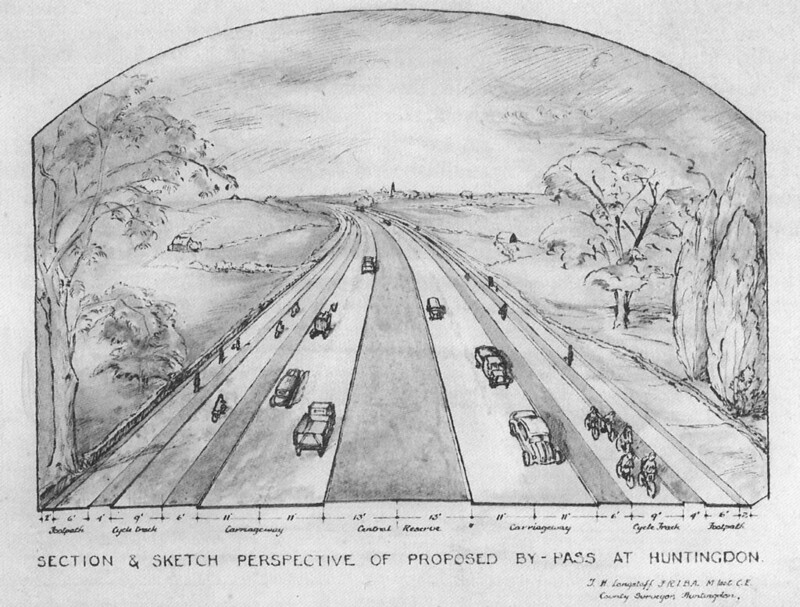

As late as 1957, T. H. Longstaff, the county surveyor for Huntingdonshire, suggested cyclists should be provided with cycleways alongside the proposed Huntingdon bypass. This was eventually built in 1973 – but without provision for cyclists.

Writing in the following year, Professor Sir Colin Buchanan, one of Britain’s key town planners and traffic engineers, said:

“The meagre efforts made to separate cyclists from motor traffic have failed, tracks are inadequate, the problem of treating them at junctions and intersections is completely unsolved, and the attitude of the cyclists themselves to these admittedly unsatisfactory tracks has not been as helpful as it might have been.”

Some bicycle advocates have suggested it was opposition of cycling organisations to the cycle path experiments of the 1930s that prevented national take-up of these paths. If only CTC and the NCU had supported the Western Avenue experiment, a Dutch-style cycle network might have later evolved, is the claim. In actual fact, cycling organisations had little to do with the failure of the bike path network. Ordinary cyclists didn’t use the paths because they weren’t very good paths, and post-war austerity meant no new paths were built, nor were existing ones improved to the standard that CTC and NCU said would be required. As well as the lack of investment from local and national Government there was also a lack of willingness to provide for anything other than motor-cars: post-war politicians and planners were deeply dismissive of cycling, blinded by the economic potential of mass motoring. Cycling, it was felt, was outmoded, not suited for the modern era, a motor era. And the great British public seemed to agree: people wanted to own and drive cars.

The highly-influential Traffic in Towns report of 1963 – the report by Professor Buchanan which town planners used to create urban motorways and pedestrian zones separated from motor traffic – mentioned cyclists only in passing, and clearly believed, desired even, that urban cycling would soon wither to nothing:

“We also considered the question of cyclists. Although in the mode of travel diagram for the year 2010 there is an allocation of movements to pedal cycles, it must be admitted that it is a moot point how many cyclists there will be in 2010…[This] does affect the kind of roads to be provided. On this point we have no doubt at all that cyclists should not be admitted to primary networks, for obvious reasons of safety and the free flow of vehicular traffic. It would make the design of these roads far too complicated to build ‘cycle tracks’ into them, nor would this be likely to provide routes convenient for cyclists in any case. It would be very expensive, and probably impracticable, to build a completely separate system of tracks for cyclists.”

Does this make you angry? It does me.