More than you think, that’s how much. During the oil crisis of the mid-1970s, the Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich published Energy and Equity, a polemic that demonstrated that having to work a certain number of hours each week to pay for an expensive form of transport was a calculation that can shock. This is a theme first explored in the 1850s, but was put so beautifully and intelligently by Illich. He is certainly worth quoting at length and below I do.

Illich also argued that apparent advances in speed were nothing of the sort, when other factors were taken into account. Fast cars weren’t as fast as they seemed because the costs to society and to the individual were far higher than ever appreciated. I was reminded of all this by a lovely conversation I had last night with Robert “Bicycle Bob” Silverman. He was one of the co-founders of Le Monde à Bicyclette, one of the world’s most influential cycle advocacy groups. Many of the campaign tactics used by advocacy groups today – such as die-ins, the carrying of bicycle-shaped oversize packages on trains and buses that don’t carry bicycles, and the riding of bicycles with plywood “skirts” to show the space taken up by cars – originated with “MAB”. Montreal now has 600kms of bike lanes, including a fully-separated cycleway that goes through the CBD, and bikes have access to certain bridges and are carried on public transit. How much of this was down to MAB? Almost all of it (well, that and Montreal’s relatively left-leaning culture). Toronto is famously unfriendly to cyclists – mayor Rob Ford didn’t have to try too hard to convince local politicians to enact anti-bicycle measures – and part of the reason is because it didn’t have MAB. (I’m not saying Montreal has perfect cycle infrastructure, it doesn’t and some of it is bi-directional, but it has more cycleways than most other North American cities.)

Illich also argued that apparent advances in speed were nothing of the sort, when other factors were taken into account. Fast cars weren’t as fast as they seemed because the costs to society and to the individual were far higher than ever appreciated. I was reminded of all this by a lovely conversation I had last night with Robert “Bicycle Bob” Silverman. He was one of the co-founders of Le Monde à Bicyclette, one of the world’s most influential cycle advocacy groups. Many of the campaign tactics used by advocacy groups today – such as die-ins, the carrying of bicycle-shaped oversize packages on trains and buses that don’t carry bicycles, and the riding of bicycles with plywood “skirts” to show the space taken up by cars – originated with “MAB”. Montreal now has 600kms of bike lanes, including a fully-separated cycleway that goes through the CBD, and bikes have access to certain bridges and are carried on public transit. How much of this was down to MAB? Almost all of it (well, that and Montreal’s relatively left-leaning culture). Toronto is famously unfriendly to cyclists – mayor Rob Ford didn’t have to try too hard to convince local politicians to enact anti-bicycle measures – and part of the reason is because it didn’t have MAB. (I’m not saying Montreal has perfect cycle infrastructure, it doesn’t and some of it is bi-directional, but it has more cycleways than most other North American cities.)

I was talking to Robert for the start of my research for Bike Boom. The crowdfunding for this went live on Kickstarter yesterday and is three-quarters of the way to my target of £6000. (Thanks to the 120 kind people who have backed it so far.)

Ivan Illich is a hero of mine and, so it turned out, he’s a hero to Robert as well. Illich died in 2002. I never got to meet him or see him talk, but Robert did. They corresponded, too. Illich was a key figure to those in the anarchist anti-car movements of the 1970s. Energy and Equity was a standard text for them. But Illich wasn’t just a cult hero to the middle class counter-culture crowd he was also mainstream enough to be supported by the bicycle industry. The PR company working for the Bicycle Association of Great Britain organised a UK speaking tour for Illich and it also paid for 1000 copies of Illich’s pamphlet which it distributed to MPs, county and city councils and other parts of the establishment.

The full text of Energy and Equity is available online but here’s an extended edited extract from this often-quoted polemic:

++++

The model American male devotes more than 1600 hours a year to his car. He sits in it while it goes and while it stands idling. He parks it and searches for it. He earns the money to put down on it and to meet the monthly installments. He works to pay for gasoline, tolls, insurance, taxes, and tickets. He spends four of his sixteen waking hours on the road or gathering his resources for it. And this figure does not take into account the time consumed by other activities dictated by transport: time spent in hospitals, traffic courts, and garages; time spent watching automobile commercials or attending consumer education meetings to improve the quality of the next buy. The model American puts in 1600 hours to get 7500 miles: less than five miles per hour. In countries deprived of a transportation industry, people manage to do the same, walking wherever they want to go, and they allocate only 3 to 8 percent of their society’s time budget to traffic instead of 28 percent. What distinguishes the traffic in rich countries from the traffic in poor countries is not more mileage per hour of lifetime for the majority, but more hours of compulsory consumption of high doses of energy, packaged and unequally distributed by the transportation industry.

The model American male devotes more than 1600 hours a year to his car. He sits in it while it goes and while it stands idling. He parks it and searches for it. He earns the money to put down on it and to meet the monthly installments. He works to pay for gasoline, tolls, insurance, taxes, and tickets. He spends four of his sixteen waking hours on the road or gathering his resources for it. And this figure does not take into account the time consumed by other activities dictated by transport: time spent in hospitals, traffic courts, and garages; time spent watching automobile commercials or attending consumer education meetings to improve the quality of the next buy. The model American puts in 1600 hours to get 7500 miles: less than five miles per hour. In countries deprived of a transportation industry, people manage to do the same, walking wherever they want to go, and they allocate only 3 to 8 percent of their society’s time budget to traffic instead of 28 percent. What distinguishes the traffic in rich countries from the traffic in poor countries is not more mileage per hour of lifetime for the majority, but more hours of compulsory consumption of high doses of energy, packaged and unequally distributed by the transportation industry.

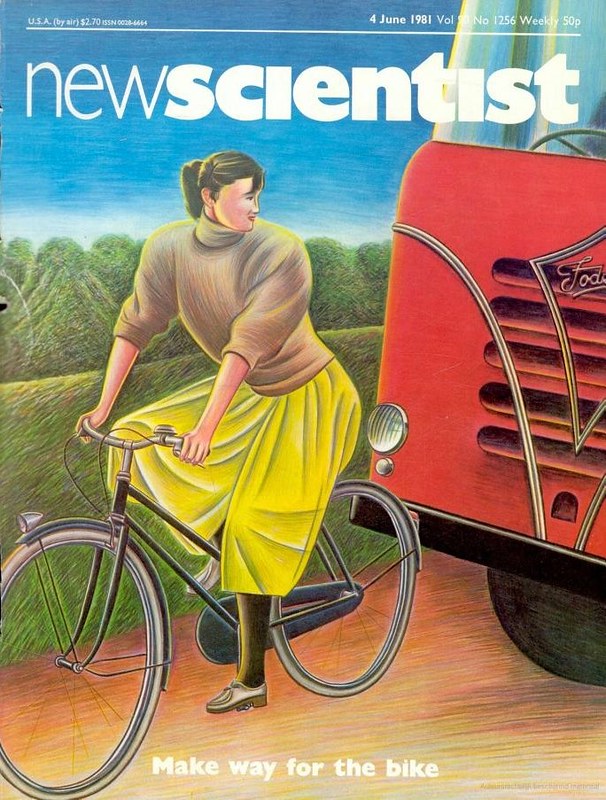

A century ago, the ball-bearing was invented. It reduced the coefficient of friction by a factor of a thousand. By applying a well-calibrated ball-bearing between two Neolithic millstones, a man could now grind in a day what took his ancestors a week. The ball-bearing also made possible the bicycle, allowing the wheel — probably the last of the great Neolithic inventions — finally to become useful for self-powered mobility.

A century ago, the ball-bearing was invented. It reduced the coefficient of friction by a factor of a thousand. By applying a well-calibrated ball-bearing between two Neolithic millstones, a man could now grind in a day what took his ancestors a week. The ball-bearing also made possible the bicycle, allowing the wheel — probably the last of the great Neolithic inventions — finally to become useful for self-powered mobility.

Man, unaided by any tool, gets around quite efficiently. He carries one gram of his weight over a kilometer in ten minutes by expending 0.75 calories. Man on his feet is thermodynamically more efficient than any motorized vehicle and most animals. For his weight, he performs more work in locomotion than rats or oxen, less than horses or sturgeon. At this rate of efficiency man settled the world and made its history.

Man on a bicycle can go three or four times faster than the pedestrian, but uses five times less energy in the process. He carries one gram of his weight over a kilometer of flat road at an expense of only 0.15 calories. The bicycle is the perfect transducer to match man’s metabolic energy to the impedance of locomotion. Equipped with this tool, man outstrips the efficiency of not only all machines but all other animals as well.

Bicycles are not only thermodynamically efficient, they are also cheap. With his much lower salary, the Chinese acquires his durable bicycle in a fraction of the working hours an American devotes to the purchase of his obsolescent car. The cost of public utilities needed to facilitate bicycle traffic versus the price of an infrastructure tailored to high speeds is proportionately even less than the price differential of the vehicles used in the two systems. In the bicycle system, engineered roads are necessary only at certain points of dense traffic, and people who live far from the surfaced path are not thereby automatically isolated as they would be if they depended on cars or trains. The bicycle has extended man’s radius without shunting him onto roads he cannot walk. Where he cannot ride his bike, he can usually push it.

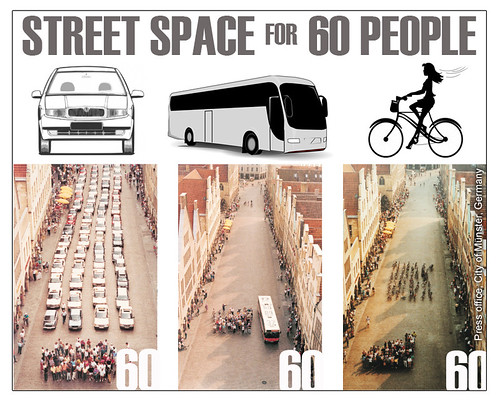

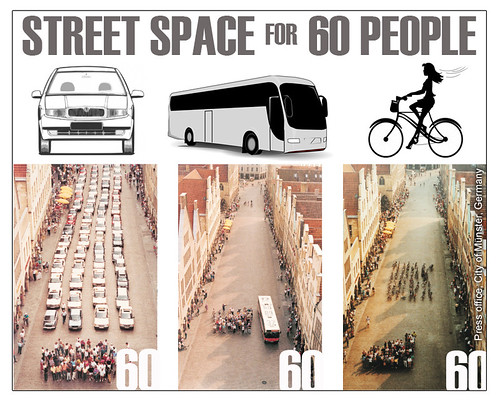

The bicycle also uses little space. Eighteen bikes can be parked in the place of one car, thirty of them can move along in the space devoured by a single automobile. It takes three lanes of a given size to move 40,000 people across a bridge in one hour by using automated trains, four to move them on buses, twelve to move them in their cars, and only two lanes for them to pedal across on bicycles. Of all these vehicles, only the bicycle really allows people to go from door to door without walking. The cyclist can reach new destinations of his choice without his tool creating new locations from which he is barred.

Bicycles let people move with greater speed without taking up significant amounts of scarce space, energy, or time. They can spend fewer hours on each mile and still travel more miles in a year. They can get the benefit of technological breakthroughs without putting undue claims on the schedules, energy, or space of others. They become masters of their own movements without blocking those of their fellows. Their new tool creates only those demands which it can also satisfy. Every increase in motorized speed creates new demands on space and time. The use of the bicycle is self-limiting. It allows people to create a new relationship between their life-space and their life-time, between their territory and the pulse of their being, without destroying their inherited balance. The advantages of modern self-powered traffic are obvious, and ignored. That better traffic runs faster is asserted, but never proved. Before they ask people to pay for it, those who propose acceleration should try to display the evidence for their claim.